Review Article

Austin Anthropol. 2023; 7(1): 1029.

The External Aesthetics of the Human Body with Anthropologic, Anatomic, Mythological, Artistic, and Neuroscientific Significance

Djulejic V1; Tomic I2; Valjarevic S3; Marinkovic L4; Marinkovic S1*; Boljanovic J1

1University of Belgrade, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Anatomy, Belgrade, Serbia

2Faculty of Art History and Muldimedia, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia

3University of Belgrade, Department of Otorhinolaryngology With Maxillofacial Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Clinical Hospital Center, Zemun, Serbia

4Department of Psychology, Cattolica University, Milan, Italy

*Corresponding author: Slobodan Marinkovic Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Anatomy, Dr. Subotic 4/2, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia. Tel: 00381112645958; Fax: 00381112645958 Email: slobodan.marinkovic@med.bg.ac.rs

Received: August 04, 2023 Accepted: September 04, 2023 Published: September 11, 2023

Abstract

The human body has several “lines of beauty:” the ventral, dorsal and lateral. Females appreciate masculinity, the expressed waist-to-chest ratio, and a Mody Mass Index (BMI) of 26 kg/m2. Males prefer the waist-to-hip ratio of 0.75, a BMI of 19 kg/m2, and larger breasts, as well as a bigger gluteal region in females. The attractive body, important for personal satisfaction and qualitative social relationships, is morphologically related to the golden proportion of 1.618. The body was painted, carved, drawn, and modeled by thousands of artists, from the Paleolithic period, some 35,000 years ago, to the present days. The body was shown either realistically, or in various forms, with a certain mythological, symbolic or conceptual meaning, and with a general or local cultural significance. Neuroscientists revealed various cortical areas and subcortical structures for body and corporal parts processing following their visual perception. The activation of these areas enables the determination of beauty and its various influences, including mood and emotions, eroticism and sexuality, mate choice, reproduction, moral attitudes, social relationships, and pleasure. Obviously, the body aesthetics has a great significance in the everyday lives of the human beings.

Keywords: Anthropology; Aesthetics; Human body; Anatomy; Fine art; Psychology

The Essence of Aesthetics

Aesthetics (from Greek aisthesis = perception), which is virtually a privilege of Homo sapiens, has mainly beauty in its focus [1–5]. It comprises perception, attention, memory, recognition, cognitive evaluation, experience, appreciation, feelings, and pleasure [6–9]. Aesthetics is mainly related to living creatures, especially humans, and various objects and ambients [10,11]. Body morphology, expressed through the golden ratio, Fibonacci sequence, and some other mathematical and geometrical laws, is the scientific basis for coroporal beauty [12–14].

Since body aesthetics has been a trait of humans for at least 35,000 years [15], it is like one of the Carl Jung’s archetypes [16], which is in fact written in our genes for ever. It means that during evolution our brain created a complex neural system for a quick and reliable recognition and appreciation of someone’s attractiveness, both subconsciously (e.g. by means of the amygdala) and consciously (by activating the cortical areas for aesthetics processing), which excites the brain reward regions [7,8].

According to the philosopher Hegel [2], the spirit is the essential prerogative of understanding aesthetics. In any case, body aesthetics has a great role in individual behavior and social interactions p6,8,17,18]. For those reasons, aesthetics is the subject of several anthropologic, psychologic, social and medical sciences and artistic creativity [2,4,15,18–21].

Aesthetics of the Body

The Trunk Aesthetics

There are general and universal morphological features as the basis of the body aesthetics [22]. Thus, the 18th century English painter Hogarth [19] described an S-shaped “line of beauty” as an important aesthetic marker of certain objects, including the human body. Two lines of beauty are seen ventrally and dorsally in the lateral view of a human figure (Figure 1). The ventral line shows developed pectoral and abdominal muscles in males, and the same muscles of a smaller volume in females, including breasts, and the subcutaneous fat tissue (Figure 1, bottom) [17,18,21]. The quadriceps femoris muscle is a caudal terminal part of this line [21].

Figure 1: Ventral and dorsal lines of beauty (bottom), with an image of the vertebral column (top). (Photo L. Marinkovic).

A dorsal line of beauty, mainly formed by the vertebral column (Figure 1, top) and the neck, back and gluteal muscles, comprises a successively arranged cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, and the prominent sacrum [21]. It is recognized in females by all persons as an aesthetic line with emotional and erotic implications, since it usually enhances someone’s attractiveness [4,17,21–25].

The vertebral column itself is a masterpiece of biological architecture [21]. In addition to our drawing [Figure 1, top], we also presented the spine and sacrum, including some other bones, of a live person in two 3D Computerized Tomographic (CT) scans (Figure 2). These images show certain aesthetic values of the human skeleton, which is the basis of the trunk morphology.

Figure 2: A 3D CT reconstruction of a volunteer’s skeleton. Note a superior view of the chest (top) and inferior view of the pelvis (bottom). (Courtesy of Dr. I. Djoric).

As for the lateral line of beauty, seen in an anterior aspect of the body (Figure 3), it is mainly related to developed deltoid, pectoral and abdominal muscles in men, including the iliac crest and the tensor fasciae latae distally. The narrow shoulders and the expressed Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) form this line in women [17,22,25]. The low WRH ratio (0.75) and the Body Mass Index (BMI) of 19 kg/m2, which corresponds to the golden ratio, associated with lower fat quantity (15-25%) distributed in the hips and the gluteal region, are very attractive for males [17,25,26]. They are probably biological signs of health and greater success in reproduction [17,18,26].

Figure 3: The body muscles in an anterior view. (Drawn by S. Marinkovic. Modified after ref. 23).

On the other hand, the Waist-to-Chest Ratio (WCR) and masculinity are especially important in male body attractiveness. In addition, the golden proportion is achieved when “the ratio of the upper body half to the lower half is equal to the ratio of the whole to the lower half” (cit. 26). When associated with a BMI of 26 kg/m2, this combination is the most attractive for females. The described morphometric examinations are an attempt for a rational and scientific explanation of someone’s physical beauty.

However, corporal beauty has to be associated with certain psychologic, anthropologic and social features to be completely appreciated aesthetically, e.g. charm, elegance, grace, harmony, the spiritual aspect, wisdom, dignity, speech quality, and body language. Simply, “The human body is not an idol of lust but an icon of soulful aesthetics and compassionate intimacy“ (cit. 4).

Artistic, Anthropologic, and Mythological Characteristics

For the mentioned reasons, many thousands of artists have presented the body so far, from the small Paleolithic Willendorf Venus and simple cave drawings, to the monumental 20 m high statues of Ramesses II in Aswan, a Chinese 71 m high Leshan Buddha, a Japanese seated Great Buddha of 15 m in height, and “The Terracotta Army” of about 8,000 life-size male statues [15,27]. The Oceanian Rapa Nui people built monumental monolith statues on the Eastern Islands, whilst the Mesoamerican cultures produced big “Atlantean Figures” [28]. Many large erotic female and male figures were created in the Khmer’s Angkor Wat [27]. The ancient Indian sculptors usually modeled statues with rounded breasts and expressed waste-to-hip ratio.

The supreme aesthetics of the body was achieved in the Greek sculptures, e.g. “Venus de Milo,” “Apollo Belvedere,” and Polykleitos’ “Doryphoros,” along with some copies and original works by later Roman artists [15]. In any case, anthropomorphic gods and deities were often modeled in monumental dimensions to show their power or sublime beauty, and their great significance for human existence.

A combination of the human body and various animals was often presented, for instance, in the Egyptian and Greek sphinx. one of which was mentioned in the famous Sophocles’ play “Oedipus Rex,” painted later by Ingres, von Stuck, and Moreau, and modeled by Rodin [3,29]. The Greek Centaur and the Assyrian Lamassu were a human-headed horse and a winged bull, respectively, whilst the Greek Satyrs were half-man and half-goat [30]. Later on, Bosch, Max Ernst, Fuseli, Magritte, and Dali depicted various combinations of humans and animals in their phantasmagoric paintings.

In addition to typical torsos, some of them were presented with bird wings, e.g. the ancient goddesses Isis and Ishtar, the god Mazda, and the Greek deities Nike, Selena and Eros [15]. There also appeared the biblical winged angels, together with previous devils, which were presented, for example, by Memling in “Music-making Angels,” and by Boilly in “Tartini’s Dream” based on the “Devil’s Trill Sonata” by Tartini [31].

Many religious artworks of the body were made in the Middle Ages [15,32]. Then started the grandiose Renaissance which resulted in Botticelli’s beautiful “The Birth of Venus,” Michelangelo’s and Donatello’s biblical “David,” Mantegna’s “St. Sebastian,” da Vinci’s “Leda,” and Dürer’s nude self-portrait [15]. In order to achieve the maximum reality and aesthetics, da Vinci, Michelangelo and Pollaiuolo performed anatomic examinations, whilst Dürer made a morphometric study of the human body.

Similar artworks appeared later on with Giorgione’s, Titian’s, Velásquez’s and Rubens’ naked “Venus,” the Bernini’s “Apollo and Daphne,” Houdon’s “The Cold Girl,” and Canova’s “Eros and Psyche” [3]. There were also the Cranach’s slim “Three Graces,” Goya’s “Majas”, and Renoir’s, Ingres,’ Delacroix’s, and Matisse’s paintings “Odalisque” [15].

Obviously, the nudity with fine proportions and sensuality dominated in Ancient Greece and Rome, but also since the Renaissance time onwards [15]. As for body proportions, Roman architect Vitruvius presented them in a man’s drawing surrounded by a square superimposed on a circle, which was modified later on by Da Vinci [33]. The golden ratio was also a parameter of the body proportions and beauty [15].

As for nude male masculinity in artworks (Figure 3), Francavilla created a beautiful statue of a running skinless male with the contracted musculature [3]. The master Pollaiuolo in his “Battle of Nudes” presented the male muscles anatomy. Fine images of the musculature were depicted by artists collaborating in illustrations of certain anatomic atlases [34–36].

Some artists modeled longer and thinner torsos of certain figures, e.g. Giacometti, Miró, Matisse, and Klee, whilst Chagall often painted long arch- or S-shaped figures flying in the air [37]. On the contrary, Bosch depicted some people without trunks. Ellis, Hepworth and Banfi designed some triangular, rhomboid, or ovoid torsos.

Around the beginning of the 20th century and later on, Gauguin’s exotic nudes were depicted, as well as Renoir’s, Cézanne’s, Metzinger’s, and Putz’s “Bathers,” and Picasso’s, Ernst’s, Chagall’s,” and Matisse’s “Red Nude” or “Blue Nude,” respectively [10]. Edvard Munch seems to be the only artist who painted a naked Virgin Mary. Archipenko and Jean Arp created simple, elegant and sensual figures of nudes [38].

The beauty of the body depends not only on its nudity. Thus, the Greek statue “Nike of Samothrace” in her wave marble tunic is the highest achievement of aesthetics. It is a similar situation with the pose and intellectual appearance of Houdon’s sculpture of Voltaire, Rodin’s grandiose statue “Balzac,” Klinger’s “The Statue of Beethoven,” and several Delacroix’s portraits of Paganini and Chopin [15]. Michelangelo’s monumental “Moses” shows an incredible mental power and physical strength.

Many modern artists gave up the imitation of reality. Thus, Picasso created first simple two-dimensional (2D) body paintings, which he soon transformed into a complete cubist style. In many drawings and cut outs, Matisse applied just two “lines of beauty” to present simplified female nudes, whilst Brancusi modeled very simple but elegant figures. Other modern artists continued with 2D or 3D painting, but in new styles, especially in symbolism and surrealism, such as in the artworks by Moreau, Fuseli, Klimt, Munch, Magritte, Dali, and others [29].

Some modern artists presented the human body in many different forms [10]. Thus, Zadkine created the sculpture “Destroyed City” with a split trunk, and Moor with a hole in the torso of some figures, whilst Magritte painted certain persons as being petrified. Léger depicted simple doll-like figures, Bottero very fat people, Paci and Masson partially dissected torsos, and Giger with a sexual connotation.

Certain artists used naked body drawings, or live bodies, as a medium for painting, e.g. Marwedel, whilst some others, e.g. Yves Klein, imprinted freshly colored nude females on canvas [38]. Ballerinas, dancers, and performance artists and actors use their own bodies for live presentations. A special type of body art is related to dissected human cadavers presented in various postures by von Hagens.

Nevertheless, the goal of artists is not only a production of morphological works, but also a presentation of the “human soul, i.e. the internal being of humans” (cit. 4).

Movement Aesthetics

Some human figures are observed or presented in certain actions. For instance, the “Discobolus” of Myron, the wind god Zephyr by Botticelli, Giambologna’s dramatic sculpture “The Rape of Sabine,” Fragonard’s “The Swing,” Degas’ ballerinas, and Chagall’s “The Promenade” [15].

However, some artists tried to present body actions more realistically, e.g. “The Swirling Scarf” by Leonard, and “Loie Fuller Dancing” by Roche. Duchamp and Balla painted multiple images of the figure “Nude Descending a Staircase,” and “Girl Running on a Balcony,” respectively [3]. Boccioni presented wing-like and elongated muscles by a strong air flow in a running figure [15]. But still, only a photograph, shot with a long exposure, can manage to catch entire movements and their beauty (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Movements of the young girls dancing on a stage. (Photo S. Marinkovic).

Neuroaesthetics

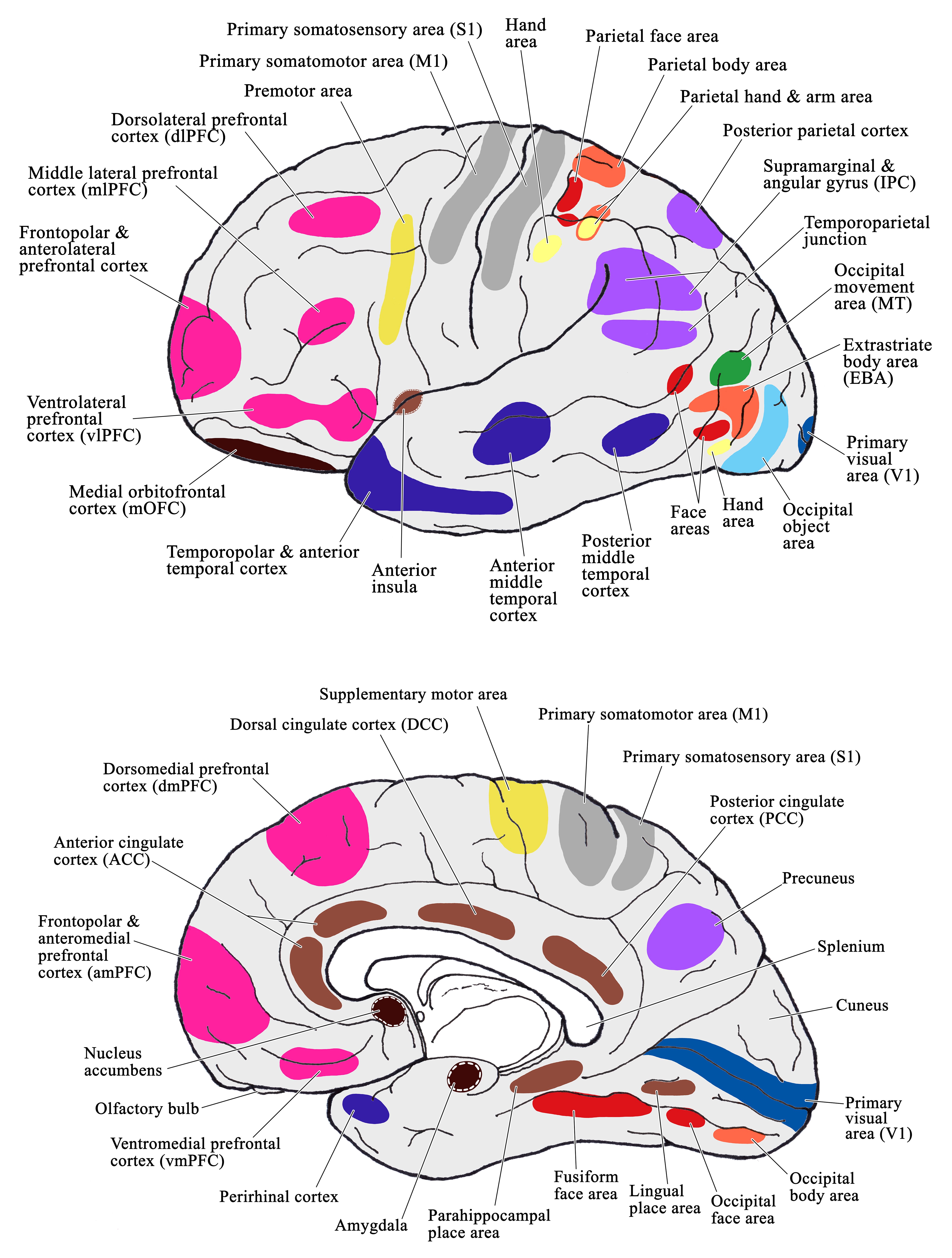

Neuroscience has determined several steps of processing and many brain regions engaged in the visual analysis of the corporal beauty [7,20,39]. The main steps comprise attention, perception, memory, recognition, aesthetic evaluation, experience and appreciation, general mood, emotions, and certain reward benefits (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Schematic drawings of the dorsolateral (top) and ventromedial surface (bottom) of the cerebral hemispheres with cortical areas and subcortical structures involved in the aesthetic processing. Note the body (orange), face (red), and hand areas (bright yellow). (Drawn by S. Marinkovic).

As for attention, both dorsal and ventral attentional systems are engaged [40]. The initial perception via the visual system is related to the primary visual area (V1). The main region of the cerebral cortex for a corporal complex processing is the Extrastriate Body Area (EBA) [41]. The EBA (Figure 5), close to the border of the lateral occipital gyri and the middle temporal cortex [42], mainly performs the processing of the body morphology, such as shape, size and posture, but also gender and age [43]. However, it is also responsible for analyzing body emotion expression, a primary aesthetic valuation, and the rating of the opposite gender [7]. The EBA sends signals, among others, to the parietal cortex, which is one of the main regions of aesthetic integration.

There is also a role of the Fusiform Body Area (FBA) in the occipital cortex (Figure 5) [43]. The nearby hippocampus, including some cortical regions, are engaged in retrieval and processing the stored body images, and novel information memorizing [44]. The insular cortex (Figure 5) is important for the inner motivational state and functional integration of emotions and mood, and for aesthetic evaluation [7]. The lateral temporal cortex also contributes to aesthetic appreciation [45].

There is also an activation of the frontopolar area and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex – dlPFC (Figure 5) [46]. The former is important for aesthetic judgment, and the latter for the body aesthetic appreciation, self-awareness, response selection, and in emotion regulation. The ventrolateral PFC – vlPFC (Figure 5) is engaged in mood and emotional regulation, and in aesthetics and morality judgments.

The ventromedial (vmPFC) and medial PFC (mPFC) (Figure 5) links moral and aesthetic valuation, and the mPFC alone is also important for socio-cognitive assessment. It is also engaged in mood and positive emotional regulation along with the posterior cingulate area [9]. The adjacent precuneus is mainly responsible for mental imagery and episodic memory retrieval. As for the anterior cingulate cortex (Figure 5), it is important, along with the mPFC, for emotional aspects of aesthetic-related responses [45]. The dorsal cingulate cortex is also involved in aesthetics analyzing (Figure 5).

General mood areas are also involved, e.g. the vmPFC and vlPFC (Figure 5). These areas, along with the EBA and MT, enhance the function of the reward structures, especially the medial orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices, putamen, caudate, ventral striatum, amygdala, and nucleus accumbens (Figure 5) ) [8,9].

There is also an engagement of the superior and inferior parietal cortices (Figure 5), which are responsible for sensorimotor integration, including the multisensory construction of body image [47]. The superior and posterior parietal areas are activated by perceiving corporal beauty [7]. The nearby temporoparietal junction is engaged in social and moral cognition, and positive emotions [40].

Body Parts Aesthetics

Head Aesthetics

Many thousands of heads were depicted so far: from the pharaoh statues, the beautiful Nefertiti bust, bearded Akkadian figures, and the Hindu god Shiva statues with 4-5 heads, to the Greek and Roman heads of their gods and others, which presented an ideal beauty [3]. The ancient Hindu Ganesha had an elephant head, the Greek Minotaur possessed a bull’s head, the Egyptian Osiris a falcon head, Anubis a canine head, and the sun god Amon-Ra curled ram horns [30]. The latter were presented in modern Nestor’s “The Satyr” and in Dali’s “Portrait of Picasso.” Besides, Cornu Ammonis is a synonym for the limbic structure hippocampus, which is crucial for memory functions [21].

Modeling and painting heads continued through the Middle Ages to the Renaissance [15], when Da Vinci analyzed and drew heads of dozens of people, and performed their morphometric study [33]. Later on, Arcimboldo painted many portraits composed of flowers, fruits, vegetables, and other items, whilst Bernini carved in marble the impressive “Damned Soul.” Thousands of portraits were depicted in the Mannerism, Baroque, and other artistic periods. Modern Dali even presented “Heads Full of Clouds,” whilst Chagall often painted heads of live people separated from their neck and usually rotated [37].

Face Aesthetics

The face is an essential and unique part of the human identity, manifesting certain personality traits and emotions, but also someone’s attractiveness [15,24]. Only a small part of someone’s face is enough to recognize a known individual (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Portraits in mirrors and on the wall in Ginza, Tokyo. (Courtesy of L. Marinkovic).

The Egyptians often painted a body en face, and the face in a profile. Later on, the Japanese depicted impressive faces of their actors, and fine masks for No plays [27]. The beautiful face of the Greek Narcissus was later painted by Caravaggio, Waterhouse, Dali, and others. His name was used to denote a sort of flower and narcissistic personality [24]. Fine faces were depicted by many artists from the Renaissance onwards [15,27]. On the other hand, Daumier, Matisse, and Bacon occasionally presented deformed faces, whilst Picasso, Braque and Gabo often painted cubistic faces. Warhol depicted several series of the faces of Mona Lisa and Marilyn Monroe in various colors [38].

The Roman God Janus was presented with two faces, whilst the Hindu Shiva had several faces [30]. Frida Kahlo made a portrait of her own face partially overlapped with Rivera’s face as a symbol of unity in love. Elongated faces were painted by El Greco, Modigliani and Rottluff, and modeled by Avramidis [15]. The beautiful minimalistic metal face “Sleeping Muse” was created by Brancusi. Thousands of portraits were presented by art photographers [48].

Some parts of the face, especially the eyes, possess their own aesthetics and have an important psychologic and social, as well as cultural significance, and symbolic meanings, e.g. the Egyptian eye of the god Horus, the large staring eyes of the Akkadian sculptures, and the Eye of God in Christianity [32]. There is a piercing stare of the Roman bust “Elder Brutus”, deterrent in Goya’s Saturn, and horrible gazes in Picasso’s “Guernica,” but a silent, sublime sorrow on the Virgin’s face in Michelangelo’s “Pieta” [15]. Beccafumi painted the two eyes of St. Lucy on a plate, which were gouged out by the Imperator Diocletian’s order [32]. Picabia presented “The Cacodylic Eye”, and Man Ray photographed tears from an eye [15]. Magritte painted “The False Mirror,” i.e. a large eye with clouds and sky inside. The mentioned god Shiva had a third eye on his forehead. The Greek Cyclops possessed a singular eye, as depicted by Reni, Poussin, Moreau, and Redon.

Sensual lips were painted, for example, in Raphael’s portrait of Simonetta. “The Kiss” was painted by Millet, Klimt, Lautrec, Manet, Magritte, Chagall, Munch and others. Canova presented a kiss of the god Eros and the princess Psyche, and Rodin modeled “The Kiss” in marble. Man Ray painted isolated large red lips in the sky. Salvador Dali used the characteristic lips morphology of Mae West to design the “Lip Sofa.” Wesselmann painted several compositions with red lips and a breast [38].

A beautiful nose was depicted by Botticelli, Raphael, and many others. A large or long nose was modeled in some Maya works, and in certain Rottluff, de Kooning and Magritte portraits, and a very small nose in Dubuffet’s paintings [15,28]. Some contemporary artists presented faces with only a nose, or the nose alone, e.g. Baldessari. Finally, Shostakovich composed a satirical opera entitled “The Nose” [31].

Among the most impressive facial expressions were those modeled by Messerschmidt [3]. Some others presented various psychological states, e.g. laughter in “The Laughing Man” of Rembrandt and “The King Drinks” by Jordaens [15]. Fear was depicted by Munch in “The Scream,” and “Melancholy” by the latter and Malczewski. There also are “Memory” by Magritte and Knopf, “Hope” by Watts and Chavannes, and happiness by Podkowinski in his “Ecstasy.”

Neck and Spine Aesthetics

Nunzio Paci depicted the neck selectively, from whose dissected brachial plexus several small branching trees originated. Certain Mannerism artists often painted a long, elegant neck, e.g. Parmigianino and El Greco, and later on Modigliani [15]. Larger neck muscles were expressed in da Vinci’s drawing of St. Jerome, Michelangelo’s “David,” and a Stiglitz photograph. Marc Quinn was the only sculptor who made some works of the torso and the head but without the neck.

Breasts

Breasts (Gr. mazos or mastos, hence mastitis) represent the secondary female sexual characteristic [21,25]. They were painted or modeled by thousands of artists, from the ancient times to the present day [3,15]. Most of them created typical breasts, e.g. Sarah Goodridge in “Beauty Revealed”. Small breasts were painted on some of Munch’s nude girls, and in Rivera’s “Maturation,” which showed a transformation of young girls into mature women. David Hamilton photographed the same subject many times [48].

Large breasts were presented in some women, including fat ones, e.g. in certain paintings by Rubens, Manet, Klimt, de Kooning, and Bottero [15]. African figures often present pyramidal or long conical breasts [3]. On the other hand, some ancient Greek artists modeled statues of the goddess Artemis (the Roman Diana) with more than a dozen breasts [30].

Some artists painted or modelled only one breast, e.g. Fouquet and modern Wesselmann [15,38]. According to a Greek legend, the female warriors Amazons used to burn their right breast in order to draw their bows more easily. Since the breast in Greek is mazos, and the negation is “a”, the word Amazon was created, i.e. someone without a breast [30]. The Amazon river got its name probably due to the participation of the local women, along with men, in the war against the Spanish conquistadors.

According to an early Christian legend, the girl Agatha was punished by her Roman suitor by excising her breasts with pincers [32]. The painter Zurbaran impressively depicted her breasts on a plate [15]. Modern Frida Kahlo painted the anatomic structure of the left breast in “My Nurse and I” [29]. Some others depicted a milk stream from the breasts, e.g. Tintoretto and Masson [3,15].

Breasts have always had a maternal, erotic, or symbolic meaning, from the Willendorf Venus, the fine Babylon’s “The Queen of the Night,” and in many Indian and Khmer sculptures, to many European artworks [15,30]. Breasts were literally described by the famous Japanese writer Yukio Mishima in his novel “The Sound of Waves.”

Arms and Hands Aesthetics

The Minoan culture in Crete made an anatomically excellent clay model of a forearm and a fist [49]. An Egyptian nude female figurine shows raised arch-shaped arms. Later on, El Greco painted St. John with arms raised towards heaven, and Goya depicted the raised arms of a Spanish victim in front of a French firing squad [15].

Hindu artists presented Vishnu, Shiva and some other deities with 4 to 10 arms (Fahr-Becker 2006). Modern Magritte painted 4 arms in “The Magician” [50]. The ancient Greek nymph Daphne was transformed into a laurel tree, starting with a branching of her arms, as beautifully modeled by Bernini [3].

Hands (Figure 7, top) were evolutionarily formed to perfection [21]. The mentioned Dürer depicted the famous “Hands of Apostle,” and Koelz “Boy’s Praying Hands” [15]. Michelangelo painted in the Sistine Chapel the hand of God pointing to the hand of Adam and thus giving life to him. Grünewald depicted Christ with raised arms and perforated hands. Rodin carved in white marble the magnificent “Hand of God” creating Adam and Eve [3].

Figure 7: Intertwined hand fingers (top), and children’s handprints on a school wall (bottom). (Photo I. Tomic).

Le Brun, Chagall and Magritte depicted their own artistic hands, Rivera painted “The Hands of Dr. Moore,” whilst Escher presented two hands as drawing each other. César made several giant sculptures of his thumb [38]. Ravel composed a piano concert only for the left hand [31]. Finally, modern wall handprints (Figure 7, bottom) are like a replication of the Paleolithic cave hand impressions [15].

Legs and Feet Aesthetics

The legs and feet of Homo sapiens are evolutionarily so designed to optimally support the body mass, but also to enable free bipedal locomotion (Figure 3). This was shown in Giacometti’s slim and elegant statue “Woman Walking” [10].

Some ancient sculptures in Mesopotamia, and later in Greece and the Roman Empire, were modeled as sirens, which were later presented with a fish tail as mermaids, for instance in the Eriksen’s sculpture “The Little Mermaid” in Copenhagen [3]. Certain artists showed isolated legs without a torso, such as Bosch, Magritte, Gober, and Giger. Some others created very long female legs, e.g. Giacometti and Biquet.

The foot (Figure 8) has a specific architecture which enables standing and a bipedal gait. A simple stone foot was a symbol of Buddhism. The mentioned Dürer beautifully depicted the plantar aspect of a pair of feet, like Dali five centuries later in “The Ascension of Christ” [51]. Mantegna painted the perforated soles of dead Christ. Degas depicted the feet of ballet dancers, whilst Magritte presented feet-like boots. A foot made of wax (Figure 8) is exhibited in the Florentine Museum “La Specola.”

Figure 8: A wax model of the foot with presented bones, joints, muscles, tributaries of the great saphenous vein, and the dorsal cutaneous nerves. (Collection of “La Specola” Museum in Florence, Italy. Credit: Museo di Storia Naturale Universita di Firenze, sez. Zoologica “La Specola” – Italia. Photo credit: Saulo Bambi – Museo di Storia Naturale/Firenze).

The Meaning and Significance of Aesthetics

Beauty is a universal essence of the aesthetics, with a certain influence of individual differences and various cultural conditions [17.39]. Its understanding and appreciation, including the beauty of the human body, is enabled by the great cognitive capabilities of Homo sapiens [7,39,44,45]. As for the artists’ presentation of the human body, there are no limitations in their creativity [15].

Nevertheless, body aesthetics has a role in biological and social adaptation, which is mainly related to mate selection and reproduction, and social interrelationships, including emotional responses [39]. “Beauty is rewarding and rewarded” (cit. 52) with both a personal and social connotation. In general, attractive persons show self-confidence, positive self-regard, and agency. They usually have economic and social advantages, e.g. a higher income and a good career. They show psychological well-being, including happiness, and life satisfaction.

In any case, the resultant mental rewards, experienced by attractive individuals and their observers, enhanced by Boucher’s “The Triumph of Venus,” Chagall’s “The Triumph of Music,” Shakespeare’s “Midsummer Night’s Dream,” and Kusama’s artwork “Beauty Will Save the World,” enable humans to enjoy aesthetics and life forever.

References

- Hartmann, Aesthetik N. Berlin: Walner de Groyter; 1953.

- Hegel GWF. Aesthetics. Lectures of fine art. New York: Oxford University Press; 1988.

- Duby G, Daval JL. Sculptures from the antiquity to the Middle Ages, and from the renaissance to the present day. Köln: Taschen; 2006.

- Levine MP. Perception of Beauty. (Rijeka: IntechOpen CC BY). 2017.

- Bian Z. Relationship between cognition of decorative folk-art and aesthetic evaluation. Revist Argent Clin Psychol. 2020; 29: 1378-85.

- Harry B, Williams MA, Davis C, Kim J. Emotional expressions evoke a differential response in the fusiform face area. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013; 7: 692.

- Kirsch LP, Urgesi C, Cross ES. Shaping and reshaping the aesthetic brain? Emerging perspectives on the neurobiology of embodied aesthetics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016; 62: 56-68.

- Young CB, Nusslock R. Positive mood enhances reward-related neural activity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016; 11: 934-44.

- Sanguinetti JL, Hameroff S, Smith EE, Sato T, Daft CMW, Tyler WJ, et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound to the right prefrontal cortex improves mood and alters functional connectivity in humans. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020; 14: 52.

- Ruhrberg K, Schneckenburger S, Fricke C, Honnef K. Art of 20th Century. Painting, sculpture, new media, photography. Köln: Taschen; 2005.

- Berleant A. The transformations of aesthetics. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publication; 2014.

- David A, Altevogt R. Golden mean of the human body. Fibonacci Q. 1979; 17: 340-4.

- Persaud D, O’Leary J. golden proportions, and the human biology. Fibonacci series. Austin J Surg. 2015; 2: 1066.

- Thapa GB, Thapa R. The relation of golden ratio, mathematics and aesthetics. J Inst Engineering. 2018; 14: 188-99.

- Davies PJE, Denny WB, Hofrichter FF, Jacobs JF, Roberts AS, Simon DL. Janson’s history of art. The western Ttradition. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. 2007.

- Jung C. Man and his symbols. Garden City: Doubleday Publishing; 1964.

- Singh D, Dixson BJ, Jessop TS, Morgan B, Dixson AF. Cross-cultural consensus for waist–hip ratio and women’s attractiveness. Evol Hum Behav. 2010; 31: 176-81.

- Wincenciak J, Fincher CL, Fisher CI, Hahn AC, Jones BC, DeBruine LM. Mate choice, mate preference, and biological markets: the relationship between partner choice and health preference is modulated by women’s own attractiveness. Evol Hum Behav. 2015; 36: 274-8.

- Hogarth W. The Analysis of Beauty. With a View of Fixing the Fluctuating Ideas of Taste. (London: Strahan W). 1753.

- Boccia M, Barbetti S, Piccardi L, Guariglia C, Ferlazzo F, Giannini AM, et al. Where does brain neural activation in aesthetic responses to visual art occur? Meta-analytic evidence from neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016; 60: 65-71.

- Standring S. Gray’s anatomy. The anatomical basis of clinical practice. London: Elsevier Limited; 2016.

- Cannizzaro S. ’The Line of Beauty:’ on natural forms and abductions. Semiotics. Ottawa: Legas Publishing; 2008.

- Vannini V, Pogliani G. The new Atlas of the human body. London: Chancellor. 1999.

- Friedman HS, Schustack MW. Personality: Classic theories and modern research. Boston: Pearson. 2005.

- Markovic S, Bulut T. Attractiveness of the female body: preference for the average or the supernormal? Psihologija. 2017; 50: 403-26.

- Naini FB, Moss JP, Gill DS. The enigma of facial beauty: Esthetics, proportions, deformity, and controversy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 130: 277-82.

- Fahr-Becker G. The art of East Asia. (Köningswinter. Könemann). 2006.

- Phillips C. The lost history of Aztec & maya. London: Anness Publishing Ltd. 2004.

- Gibson M. Symbolism. Köln: Taschen. 2006.

- Guirand F. Schmidt J. Mythes & mythologie. Histo¬ire et dictionnaire. Paris: Larousse. 1996.

- Alberti L. Musica nei secoli. Milano: Arnold Mondadori Editore). 1972.

- Ferguson G. Signs and symbols in Christian Art. London: Oxford University Press. 1989.

- Nathan J. Anatomical drawings. In: da Vinci L, editor. The complete paintings and drawings. F. Zöllner, ed. (Köln: Taschen). 2007; 400-79.

- Pernkopf E. Atlas of topographical and applied human anatomy. 1963. (Phila¬delphia: W. B. Saunders Company). 1963.

- Saunders deCMJB, O’Malley CD. The illustrations from the works of Andreas Vesalius of brussels. New York: Dover Publications Inc. 1973.

- le Minor JM, Sick H. The Atlas of Anatomy and Surgery by J.M. Bourgery and N.H. Jacob – A Monumental Work of the 19th Century. Köln: Taschen; 2005.

- Chagall B-TJ. Köln: Taschen. 2003.

- Lucie-Smith E. Art Today. From abstract Expressionism to superrealism. New York: William Morrow; 1977.

- Jacobsen T. Beauty and the brain: culture, history and individual differences in aesthetic appreciation. J Anat. 2010; 216: 184-91.

- Igelström KM, Webb TW, Kelly YT, Graziano MSA. Topographical organization of attentional, social, and memory processes in the human temporoparietal cortex. Neuropsychol. 2017; 105: 70-83.

- Amoruso L, Couto B, Ibáñez A. Beyond extrastriate body area (EBA) and Fusiform Body Area (FBA): context integration in the meaning of actions. Front Hum Neurosci. 2011; 5: 124.

- Gandolfo M, Downing PE. Causal evidence for expression of perceptual expectations in category-selective extrastriate regions. Curr Biol. 2019; 29: 2496-2500.e3.

- Carey M, Knight R, Preston C. Distinct neural response to visual perspective and by size in the extrastriate body area. Behav Brain Res. 2019; 372: 112063.

- DiDio C, Ardizzi M, Massaro D, Di Cesare G, Gilli G, Marchetti A, et al. Human, nature, dynamism: the effects of content and movement perception on brain activations during the aesthetic judgment of representational paintings. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016; 9: 1-19.

- Vessel EA, Isik AI, Belfi AM, Starr GG. The default-mode network represents aesthetic appeal that generalizes across visual domains. PNAS. 2019; 116: 19155-64.

- Ticini LF. The role of the orbitofrontal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices in aesthetic preference for art. Behav Sci (Basel). 2017; 7: 31-9.

- Huang RS, Chen C, Tran AT, Sereno MI. Mapping multisensory parietal face and body areas in humans. PNAS. 2012; 109: 18114-9.

- Misselbeck R. 20th century Photography. Museum Ludwig cologne. Köln: Taschen; 2007.

- Persaud TVN. Early History of Human Anatomy. From Antiquity to the Beginning of the Modern Era. (Springfield: Charles C. Thomas Publishers). 1984.

- René Magritte MJ. Köln: Taschen; 2007.

- Descharnes R, Nerét G, Dali S. Köln: Taschen; 2006.

- Datta Gupta N, Etcoff NL, Jaeger MM. Beauty in mind: the effects of physical attractiveness on psychological well-being and distress. J Happin Stud. 2015; 17: 1313-25.