Research Article

Int J Nutr Sci. 2022; 7(2): 1067.

Do Individuals Consulting for Binge Eating Behaviors Have Similar Psychosocial Functioning Across Different Eating Disorders?

Sinturel S¹, Gagnon C², Bournival C¹, Guèvremont G³ and Aimé A2,4*

1Clinique des Troubles de l’Alimentation, 1555 boulevard de l’Avenir, suite 206, Laval (QC), H7S 2N5, Canada

2Clinique Imavi, 733 boulevard St Joseph, suite 200, Gatineau (QC), J8Y 4B6, Canada

3Clinique MuUla, 74 rue Holtham, Hampstead (QC), H3E 3N4, Canada

4Department of Psychoeducation and Psychology, Université du Québec en Outaouais, Campus de Saint-Jérôme, Canada

*Corresponding author: Aimé A Université du Québec en Outaouais, Campus de Saint-Jérôme, Département de Psychoéducation et de Psychologie, 5 rue Saint-Joseph, Saint-Jérôme, Québec, J7Z 0B7, Canada

Received: November 04, 2022; Accepted: December 16, 2022; Published: December 22, 2022

Abstract

Although common characteristics have been highlighted between different Eating Disorders (ED), most existing classifications continue to consider them as separated diagnoses and to put forward their differences. The aim of this study was to verify if similarities and differences in terms of psychosocial functioning could be found between five groups of individuals, who reported binge eating behaviors. Nine hundred and seventy-eight patients consulting for ED problems in three different private clinics completed online questionnaires after a first psychological consultation. Based on their responses to the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q6), participants were included in five clinical groups: bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, anorexia nervosa binge eating/purging type, other specified feeding or eating disorders, and no binge eating behaviors. They filled out online questionnaires assessing perfectionism, self-esteem, body esteem, depression, anxiety, alexithymia, fear of negative appearance, and weight stigmatization. Significant differences were observed between the ED groups and the no binge eating behaviors’ group. Although the various ED subtypes did not differ on any of the variables studied, some clinical profiles seemed to emerge. The results support a transdiagnostic and dimensional approach to ED.

Keywords: psychosocial functioning, eating disorders, subtypes, binge eating behaviors, similarities and differences

Introduction

Binge eating behavior, characterized by the consumption of a large quantity of food in a relatively short period and a feeling of loss of control, is associated with a strong feeling of distress, which can lead to a desire to seek help [1]. This behavior is widespread in the non-clinical female population but is also common in people with Eating Disorders (ED), such as Bulimia Nervosa (BN), Binge Eating Disorder (BED), Anorexia Nervosa Binge eating/Purging type (ANBP), or Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorders (OSFED) [2].

Previous research has shown that binge eating behaviors are associated with functional impairment and comorbid psychopathology [3]. For example, the intensity of depressive symptoms correlates with disordered eating severity [4]. The Perfectionist Model Of Binge Eating (PMOBE) has been suggested as a framework to help better understand how some personality traits and contextual conditions may play a role in the occurrence of binge eating behaviors [3]. Building on the three-factor interactive model of binge eating [5], the PMOBE states that two pathways should be considered in order to explain binge eating behaviors. In the first pathway, socially prescribed perfectionism would lead first to interpersonal difficulties, then to depressive affect, and finally, to binge eating behaviors as a maladaptive coping response. In the second pathway, socially prescribed perfectionism would lead to lower interpersonal esteem and then to food restriction, which would in turn accentuate the risk of presenting binge eating behaviors [3].

In individuals with Eating Disorders (ED), the transdiagnostic model of ED has been suggested by Fairburn et al. [6]. This model posits that individuals with ED have extreme concerns about their weight and shape, which lead them to be affected by slight weight changes, to scrutinize their body, and to compare their appearance with other people [6]. To reach a desired weight and shape, they tend to place rigid and inflexible demands on themselves, especially through dietary restrictions. However, intense dietary restrictions and emotions place them at a higher risk of resorting to binge eating and compensatory behaviors. In line with the transdiagnostic approach, Vervaet et al. [7] identified common vulnerability factors in a sample of 2,302 patients seeking help for ED in a specialized center. They found that hypervigilance and inhibition of emotions and feelings to avoid making mistakes, disconnection and rejection, impaired autonomy, anxiety, and perfectionism were key factors associated with ED. Moreover, recognition and identification of appetite and emotional cues were compromised in the patients they studied. Emotion regulation processes in individuals with ED have also been highlighted by other researchers [8,9].

Hilbert et al. [10] argued that some risk factors of ED may be general, whereas others may be more specific, and that diagnosis-specific risk profiles should be identified. While comparing individuals with AN, BN, and BED, they observed both differences and similarities. In terms of similarities, they suggested possible shared etiological pathways between BN and AN and similar behavioral profiles (e.g., strict food restriction behavior), but also between BN and BED (e.g., recurrent binge eating). In terms of differences, they found that the AN and BED diagnoses seemed more distant and distinct, and that the BN diagnosis seemed to occupy an intermediate position between AN and BED. For their part, Boujut et al. [11] observed that major depressive disorder and specific phobias were found more frequently in AN than in BN. Although the differences were not significant, the authors highlighted trends and suggested that the risks of comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms were unevenly distributed between the various forms of ED. Danner et al. [12] found differences regarding emotional regulation and impulse control between the restrictive AN subtype and other ED, such as AN Binge-Purging subtype (ANBP), BN, and BED. They noted the importance of considering ED types in emotional regulation research rather than all ED as part of a same group.

Available studies where the psychosocial functioning of individuals with different types of ED was compared have limitations that should be considered. In fact, most of the samples used were relatively small [11,12] or were composed solely of a clinical population recruited in hospital settings [7]. Additionally, available studies tend to only focus on AN and BN [9] and few include the diagnostic of OSFED, despite it representing a large proportion of the persons who have ED [12].

The aim of this study was to assess shared and specific risk factors among individuals with four different types of ED (BN, BED, ANBP, and OSFED) and who all share a tendency for Binge Eating Behaviors (BEB), a core feature of ED. A fifth group, composed of individuals consulting for eating and weight preoccupations but not reporting any BEB, was included. Six variables likely to contribute to BEB and ED were assessed: Perfectionism, self-esteem, body esteem, depressive symptoms, fear of negative appearance, and internalized weight stigma. Anxiety symptoms were also included since anxiety was found to be an important factor in the development and maintenance of BEB [13,14]. Finally, alexithymia was considered because emotional regulation difficulties in people with ED have been observed in previous studies [6,8,9].

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 978 participants (n = 915 women) seeking help for eating and weight preoccupations at three private clinics in Québec, Canada (i.e., Gatineau, Longueuil, Montréal). The participants were categorized into five groups based on their answers to the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire-6 (EDEQ-6) [15]. The following question of the EDEQ-6 allowed to determine whether or not they reported binge eating behaviors: “Over the last 28 days, on how many days have you eaten an unusually large amount of food and have had a sense of loss of control?”. Participants reporting no Binge Eating Behaviors (BEB) were included in the control group: no BEB (n = 200). In total, 215 participants were classified in the BN group, 25 in the ANBP group, 346 in the BED group, and 192 in the OSFED group. The participants’ average age was 35.60 years (SD = 12.25; Mage women = 35.35; Mage men = 39.14) and their mean body mass index (BMI = kg/m²) was 31.51 (SD = 9.44; MBMI for women = 31.21; MBMI for men = 35.98).

Procedure

After a first individual meeting with a psychologist or a psychotherapist, the participants were asked to complete online questionnaires. The questionnaire completion was voluntary and lasted 60 minutes on average. Each participant could get a feedback on their individual results. This clinical study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Université du Québec en Outaouais (Protocole number: 219-193).

Measures

Disordered Eating Behaviors

The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [15,16] measures behaviors and attitudes typically associated with eating problems, in the last 28 days. It has 28 items, but only six were used for this study, to evaluate the presence and frequency of binge eating and purging behaviors.

Self-Esteem

The French version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES) [17,18] was used in this study to assess the degree of global self-esteem. This questionnaire contains 10 items (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) that are answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).In this study, the subscale showed good internal consistency (a = .89).

Body Esteem

The Body Esteem Scale (BES) [19] is a 23-item scale that measures body esteem in adolescents and adults. It has three subscales: BE-Appearance (appreciation of self-appearance), BEWeight (satisfaction with one’s own weight), and BE-Attribution (evaluations attributed to others about one’s body and appearance). Only the first two subscales of the BES were used in this study: BE-Appearance (10 items, e.g., “I worry about the way I look”) and BE-Weight (8 items, e.g., “I am satisfied with my weight”). The response scale consists of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). In this study, the two selected subscales showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90 for BE-Appearance and 0.87 for BE-Weight).

Anxiety

The T-Anxiety Subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [20,21] contains 20 items that measure relatively stable aspects of anxiety proneness (e.g., “I worry too much over something that really doesn’t matter”). The response scale consists of a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). In this study, the subscale showed excellent internal consistency (a = 0.92).

Weight Stigma

The Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire (WSSQ) [22] assesses two aspects of internalized weight stigma: self-devaluation (e.g., “I caused my weight problems”) and fear of enacted stigma (e.g., “I feel insecure about others’ opinions of me”). Each subscale contained six items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). In this study, the self-devaluation subscale showed good internal consistency (a =0.82) and the fear of enacted stigma subscale showed acceptable internal consistency (a =0.79).

Perfectionism

The Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS) [23] assesses perfectionism. It covers six dimensions: Concern over making mistakes (9 items), Personal standards (7 items), Parental expectations (5 items), Parental criticism (4 items), Doubts about actions (4 items), and Organization (6 items). This questionnaire contains 35 items (e.g., “People will probably think less of me if I make a mistake” and “I have extremely high goals”) that can be answered on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this study, the internal consistency of the FMPS is excellent (a =0.91).

Fear of Being Negatively Evaluated

The Fear of Negative Appearance Evaluation Scale (FNAES) [24] assesses participants’ fears of having their physical appearance negatively evaluated by others. The French version of this questionnaire [25] contains five items (e.g., “I am concerned about what other people think of my appearance”) answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). In this study, the FNAES showed excellent internal consistency (a = 0.94).

Alexithymia

The Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) [26] assesses difficulties identifying and describing emotions. This questionnaire contains 20 items (e.g., “I am often confused about what emotion I am feeling”). The response scale consists of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this study, a good internal consistency was found for this questionnaire (a = 0.85).

Depressive Symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression Scale (CES-D) [27,28] is a 20-item measure that assesses depressive symptoms over the past week with items phrased as self-statements (e.g., “I felt hopeful about the future”). Ratings are based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time [less than 1 day]) to 3 (most or all of the time [5–7 days]).In this study, the subscale showed acceptable internal consistency (a = 0.72).

Data Analysis

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed in IBM SPSS 26 to test differences in psychosocial characteristics between the five groups (0- absence of BEB, 1- ANBP, 3- BN, 4- BED, 5- OSFED). Next, a discriminant function analysis was used to assess the participants’ clinical profiles based on the combination of the dependant variables.

Results

Psychosocial Differences between Groups

When Pillai’s trace was used, the MANOVA indicated a statistically significant effect of the five groups on psychosocial characteristics, V = 0.29, F(40,3728) = 7.252; p < 0.001. Separate univariate ANOVAs (Table 1) performed on the outcome variables revealed which groups differed significantly from one another. Compared to participants with a diagnosis of BN, BED, or OSFED, patients without BEB presented a more positive body esteem related to their appearance (F(4,938) = 12.360; p < 0.001; η² = 0.05) and their weight (F(4,938) = 9.; p < 0.001; η² = 0.07) and less self-devaluation because of their weight (F(4,938) = 20.915; p < 0.001; η² = 0.08). Moreover, compared to all four ED groups (ANBP, BN, BED, and OSFED), participants with no BEB were less likely to report experiences of stigmatization with regard to their weight (F(4,938) = 9.622; p < 0.001; η² = 0.04) or fear of being negatively evaluated because of their appearance (F(4,938) = 14.163; p < 0.001; η² = 0.06). They also reported higher self-esteem (F(4,938) = 16.701; p < 0.001; η² = 0.07), less difficulty identifying and verbally expressing their emotions (F(4,938) = 26.958; p < 0.001; η² = 0.10), less perfectionism (F(4,938) = 11.784; p < 0.001; η² = 0.05), less anxiety (F(4,938) = 22.456; p < 0.001; η² = 0.09), and less severe depressive symptoms (F(4,938) = 24.759; p < 0.001; η² = 0.10).

No Eating disorder

Anorexia nervosa binge purge subtype

Bulimia nervosa

Binge eating disorder

Other specified feeding or eating disorders

M(SD)

M(SD)

M(SD)

M(SD)

M(SD)

BE-Appearancea

1.40 (0.80)

1.22 (0.62)

1.03 (0.71)

0.98 (0.62)

1.12 (0.64)

BE-Weighta

1.02 (0.82)

1.19 (0.51)

0.82 (0.72)

0.58 (0.50)

0.82 (0.65)

WSSQ - Self-Devaluationa

19.15 (5.39)

20.63 (4.63)

22.37 (4.66)

22.90 (4.07)

21.22 (5.06)

WSSQ - Fear of enacted stigmab

17.01 (5.10)

19.38 (3.63)

18.91 (4.75)

19.66 (4.38)

18.74 (4.93)

FNAES global scoreb

16.65 (5.59)

20.00 (4.19)

20.25 (4.54)

18.55 (5.04)

17.98 (4.62)

RSES global scoreb

30.68 (6.16)

24.63 (4.99)

26.47 (5.83)

28.48 (5.49)

28.85 (5.23)

TAS-20 global scoreb

47.99 (11.88)

58.42 (10.53)

58.99 (10.36)

52.74 (11.67)

50.60 (11.64)

FMPS global scoreb

104.63 (20.33)

120.21 (16.55)

117.13 (18.86)

111.02 (19.95)

109.19 (19.33)

STAI (T-Anxiety) scoreb

45.96 (10.19)

57.75 (7.75)

54.50 (10.00)

49.93 (10.12)

49.12 (9.44)

CES-D global scoreb

16.51 (10.51)

28.33 (10.74)

25.88 (11.21)

19.74 (10.27)

19.16 (10.38)

aSignificant statistical differences p < .001; between no ED group and the other three groups: BN, BED, and OSFED

bSignificant statistical differences p < .001; between no ED group and the other four groups: ANBP, BN, BED, and OSFED

Table 1: Means and Standard Deviations for Each Groups.

Discriminant Function Analysis

The discriminant function analysis revealed four functions. The first explained 62.9% of the variance, canonical R² = .42; the second explained 31.8%, canonical R² = .31; the third explained only 4.4%, canonical R² = .12; and the fourth explained only 0.8%, canonical R² = .05. When combined, the four functions differentiated the groups significantly, ∧= 0.73, Χ² (40) = 290.813, p < 0.001. When the first function was removed, the three others also differentiated the groups significantly, ∧= 0.89, Χ² (27) = 111.425, p < 0.001. With the second function removed as well, the third one did not differentiate the groups significantly, ∧= 0.98, Χ² (16) = 16.339, p > .05, nor did the fourth function when the third one was removed, ∧= 1.00, &chi² (7) = 2.66, p > .05.

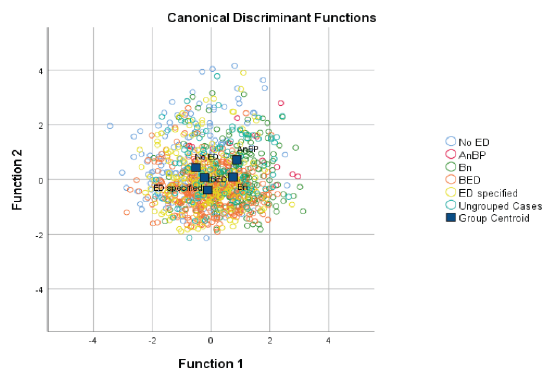

Based on the significant chi-squared values, only the first and the second functions were maintained in the analysis. The correlations between outcomes and the discriminant functions (Table 2) revealed that six variables loaded highly onto the first function: alexithymia (r = .73), depressive symptoms (r = .70), anxiety (r = .66), self-esteem (r = –.56), fear of negative appearance evaluation (r = .51), and perfectionism (r = .47). One variable (i.e., fear of being stigmatized because of weight) was forced onto the first function because the fourth one was not retained in the analysis. This function seemed to group mental health risk factors together. The no BEB group tended to be on the negative end of the first dimension (mental health), whereas the ANBP group was on the positive end (Figure 1). The OSFED and BED groups were close to the middle of the first dimension but a little more on the negative side, close to the no BEB group. The BN group was in the positive range of the first dimension, close to ANBP. Taken together, these results suggested that the no BEB group presented less severe mental health problems, whereas the ANBP and the BN groups reported more severe mental health difficulties.

Figure 1: Canonical Discriminant Functions.

Functions

1

2

3

4

TAS-20-Global

.726*

-0.173

0.112

0.186

CES-D-Global

.704*

-0.006

-0.214

0.058

STAI (T-Anxiety)

.657*

-0.113

-0.449

0.171

RSES-Global

-.555*

0.139

0.519

-0.093

FNAES-Global

.512*

-0.212

-0.084

-0.181

FMPS-Global

.472*

-0.137

-0.253

0.129

BE-Weight

-.004

.822*

-0.046

0.092

BE-Appearance

-.248

.593*

0.276

0.551

WSSQ-Self-Devaluation

.317

-.794*

-0.173

-0.093

WSSQ-Fear of enacted stigma

.178

-0.520

-.604*

0.144

Pooled within-groups correlations between discriminating variables and standardized canonical discriminant functions

Variables ordered by absolute size of correlation within function.

Variables ordered by absolute size of correlation within function.

*Largest absolute correlation between each variable and any discriminant function

Table 2: Structure Matrix.

The four variables that loaded onto the second function were: body esteem weight (r = .85), body esteem appearance (r = –.79), self-devaluation because of weight (r = –.79), and experiences of weight stigmatization (r = –.52). This second function seemed centered on preoccupations related to weight and appearance. The ANBP group tended to be on the positive end and the OSFED group tended to be on the negative end (Figure 1). More specifically, the ANBP and the no BEB groups seemed to present fewer preoccupations than the other groups regarding weight and appearance, whereas the BED and BN groups were in the middle of this dimension.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess whether or not five groups of individuals seeking help for eating and weight preoccupations differed with regard to their psychosocial functioning. Four groups of individuals with ED reporting binge eating behaviors and one control group without binge eating behaviors were compared on perfectionism, self-esteem, body esteem, depressive symptoms, fear of negative appearance, internalized weight stigma, anxiety, and alexithymia. Participants with a diagnosis of BN, BED, or OSFED reported a more negative body esteem related to their appearance and higher weight self-devaluation compared to participants with no BEB. In addition, compared to patients without BEB, those in the four ED groups (ANBP, BN, BED, and OSFED) reported a significantly greater fear of being stigmatized because of their weight, lower self-esteem, as well as higher levels of alexithymia, perfectionism, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Along the same lines, Boujut et al. [11] found that anxiety-depressive disorders are much more present in people with AN and BN than in the general population. Difficulties identifying and expressing emotions [8] and body dissatisfaction [29] were also found to be higher in individuals with ED than in those without ED.

Taken together, these results support Fairburn et al.’s transdiagnostic model [30], according to which a dysfunctional selfevaluation pattern can be found in people with ED. No matter their specific type of ED, these people would be at higher risk of pathological perfectionism and low self-esteem [30] than those who report BEB without having a specific ED diagnosis. Individuals with ED would also tend to present anxiety, sadness, anger, and intolerance in the face of unpleasant emotions. Thus, interventions intended for ED patients, could benefit from a transdiagnostic approach and may not need to be tailored to a specific ED diagnosis [7].

However, the discriminant function analysis revealed some different trends between the ED groups in terms of mental health and weight and appearance preoccupations. In particular, the ANBP and BN groups stood out from the other groups (BED, OSFED, and no BEB) in terms of mental health problems. These results are consistent with Hilbert et al.’s conclusions [10], according to which (1) AN and BN share etiologic pathways and similar behavioral profiles, (2) AN and BED diagnoses are more distant and distinct than AN and BN, and (3) BN may occupy an intermediate position between AN and BED. The severe mental health issues found in ANBP could also be attributable to medical complications following starvation [31] and may contribute to the longer duration and higher complexity of AN treatment [32].

Additionally, the ANBP group, just like the no BEB group, appeared to be less concerned about weight and appearance, whereas the OSFED group was more concerned, and the BN and BED groups were in the middle of that dimension. Given that previous research has shown that a higher body mass index in interaction with being a woman puts individuals at higher risk of developing and maintaining ED [33], it makes sense that the participants with BN, BED, or OSFED in this sample reported being more preoccupied with their weight and appearance than those with AN. In a culture that promotes slenderness and where individuals with higher weight are more likely to be stigmatized for their weight [33], individuals with AN and without BEB may feel less pressure to lose weight and to avoid repetition more comfortable with their appearance.

This study has certain limitations that should be mentioned. Firstly, the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample were quite homogeneous, with the large majority of the participants being white working women who could afford to consult in private settings. This larger representation of women may be due to the fact that men are generally reluctant to seek help for mental health problems [34]. Moreover, the fact that they had to pay for their psychological consultation could mean that the participants were, as a whole, more functional and more motivated to modify their eating patterns. Such homogeneity can increase the likelihood of finding similarities between the groups under study and can also affect generalization of the results to other populations. Generalization is also limited by the fact that there were only 25 participants in the ANBP group as opposed to much higher numbers of participants in the other groups. Additionally, as binge eating behaviors are generally associated with a higher prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders in adults [35], having only selected individuals who binge eat may have hindered possible group differences.

The results of this study support a transdiagnostic and dimensional approach according to which different ED share common characteristics and core underlying mechanisms [7,29,30]. Such an approach helps in understanding the migration observed between different ED diagnoses as well as the heterogeneity found in each ED category [7]. It also suggests interventions can be applied to individuals with ED, no matter their diagnosis. However, the results also highlighted that ANBP and BN groups present higher mental health difficulties than other ED groups, such as BED and OSFED. Higher psychopathology and eating symptomatology in individuals with AN and BN can accentuate their likelihood of presenting severe and enduring ED, which has been associated with poorer treatment outcomes [36]. Taken together, these results suggest that comorbid psychopathology and psychosocial functioning need to be assessed and included in the treatment of ED. For example, anxiety and depressive symptoms should be considered, and weight concerns, perfectionism, as well as emotional difficulties should be systematically addressed.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The clinical data used in this article are of a confidential nature and therefore cannot be made available. Participants agreed to complete the questionnaires for clinical purposes only.

References

- Waller G. The psychology of binge eating. Fairburn CG, Brownell KD, editors. In: Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. 2002; 98-102

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, text revision. American Psychiatric Association. 2022.

- Sherry SB, Hall PA. The perfectionism model of binge eating: Tests of an integrative model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009; 96: 690-709.

- Godart N, Radon L, Léblé N, L’humeur, Aimé A, Maïano C, Ricard MM, editors. In: Les troubles des conduites alimentaires: Du diagnostic aux traitements. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal. 2020; 139-150.

- Bardone-Cone AM, Joiner TE, Crosby RD, Crow SJ, Klein MH, Le Grange D, et al. Examining a psychosocial interactive model of binge eating and vomiting in women with bulimia nervosa and subthreshold bulimia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008; 46: 887-894.

- Fairburn G. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press. 2008.

- Vervaet M, Puttevils L, Hoekstra RH, Fried E, Vanderhasselt MA. Transdiagnostic vulnerability factors in eating disorders: A network analysis. European eating disorders review. 2021; 29: 86- 100.

- Aimé A, Cyr C, Ricard MM, Guèvremont G, Bournival C. Alexithymie et psychopathologie chez des femmes qui consultent pour des problèmes d’alimentation. Revue québécoise de psychologie. 2016; 37: 115-131.

- Puttevils L, Vanderhasselt MA, Horczak P, Vervaet M. Differences in the use of emotion regulation strategies between anorexia and bulimia nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2021; 109: 152262.

- Hilbert A, Pike KM, Goldschmidt AB, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG, Dohm FA, et al. Risk factors across the eating disorders. Psychiatry research. 2014; 220: 500-506.

- Boujut E, Koleck M, Berges D, Bourgeois ML. Prévalence de troubles anxiodépressifs dans une population de 169 patientes con sultant pour un trouble du comportement alimentaire (TCA) et comparaisons entre les quatre sous-types de TCA. Annales Médico- psychologiques, revue psychiatrique. 2012; 170: 52-55.

- Danner UN, Sternheim L, Evers, C. The importance of distinguishing between the different eating disorders (sub) types when assessing emotion regulation strategies. Psychiatry Research. 2014; 215(3): 727-732.

- Aimé A, Guitard T, Grousseaud L, Dugas MJ, L’anxiété, Aimé A, Maïano C, Ricard MM, editors. In: Les troubles des conduites alimentaires: Du diagnostic aux traitements. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal. 2020; 99-111.

- Rosenbaum DL, White KS. The relation of anxiety, depression, and stress to binge eating behavior. Journal of Health Psychology. 2015; 20: 887-898.

- Fairburn C, Cooper Z, O’Connor M. Eating disorders examination (16.0D). Fairburn C, editor. In: Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press. 2008; 265-308.

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The eating disorder examination. Fairburn CG, Wilson, G, editors. In: Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. Guilford Press. 1993; 317-360.

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. 1965.

- Vallières EF, Vallerand RJ. Traduction et validation canadiennefrançaise de l’échelle de l’estime de soi de Rosenberg. International journal of psychology. 1990; 25: 305-316.

- Mendelson BK, Mendelson MJ, White DR. Body-esteem scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of personality assessment. 2001; 76: 90-106.

- Gauthier J, Bouchard S. Adaptation canadienne-française de la forme révisée du State–Trait Anxiety Inventory de Spielberger. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 1993; 25: 559-578.

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press. 1983.

- Lillis J, Luoma JB, Levin ME, Hayes SC. Measuring weight selfstigma: the weight self-stigma questionnaire. Obesity. 2010; 18: 971-976.

- Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive therapy and research. 1990; 14: 449- 468.

- Lundgren JD, Anderson DA, Thompson JK. Fear of negative appearance evaluation: Development and evaluation of a new construct for risk factor work in the field of eating disorders. Eating Behaviors. 2004; 5: 75–84.

- Maïano C, Morin AJ, Monthuy-Blanc J, Garbarino JM. Construct validity of the Fear of Negative Appearance Evaluation Scale in a community sample of French adolescents. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2010; 26: 19-27.

- Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, Parker JD. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-II. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1994; 38: 33-40.

- Morin AJ, Moullec G, Maiano C, Layet L, Just JL, Ninot G. Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in French clinical and nonclinical adults. Revue d’epidemiologie et de santepublique. 2011; 59: 327-340.

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement. 1977; 1: 385-401.

- Rochaix D, Gaetan S, Bonnet A. Troubles alimentaires, désirabilité sociale, insatisfaction corporelle et estime de soi physique chez des étudiantes de première année. Annales Médico-psychologiques. 2017; 175: 363-369.

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour research and therapy. 2003; 41: 509-528.

- Mehler PS, Brown C. Anorexia nervosa–medical complications. Journal of eating disorders. 2015; 3: 1-8.

- Kelly AC, Carter JC. Eating disorder subtypes differ in their rates of psychosocial improvement over treatment. Journal of Eating Disorders. 2014; 2: 1-10.

- Jahrami H, Saif Z, Faris MEAI, Levine MP. The relationship between risk of eating disorders, age, gender and body mass index in medical students: a meta-regression. Eating and Weight Disorders- Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. 2019; 24: 169-177.

- Lynch L, Long M, Moorhead A. Young men, help-seeking, and mental health services: exploring barriers and solutions. American journal of men’s health. 2018; 12: 138-149.

- Pinheiro AP, Nunes MA, Barbieri NB, Vigo Á, Aquino EL, Barreto S, et al.Association of binge eating behavior and psychiatric comorbidity in ELSA-Brasil study: Results from baseline data. Eating behaviors. 2016: 23: 145-149.

- Treasure J, Stein D, Maguire S. Has the time come for a staging model to map the course of eating disorders from high risk to severe enduring illness? An examination of the evidence. Early intervention in psychiatry. 2015; 9: 173-184.